Whitewashing History, and Why We Need To Do Better

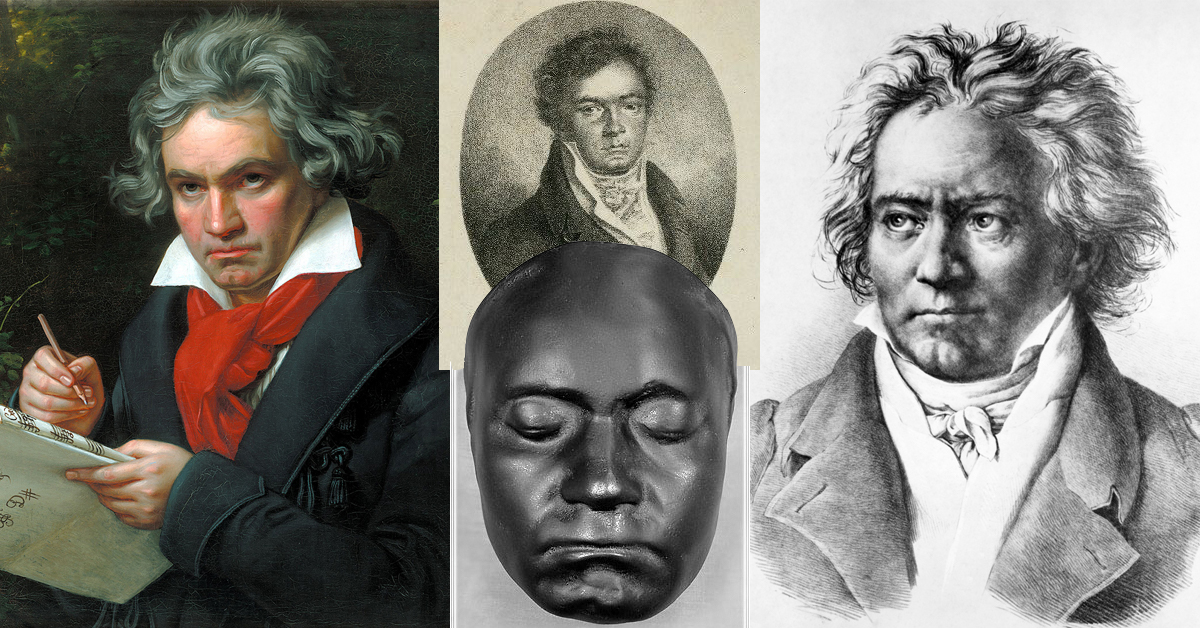

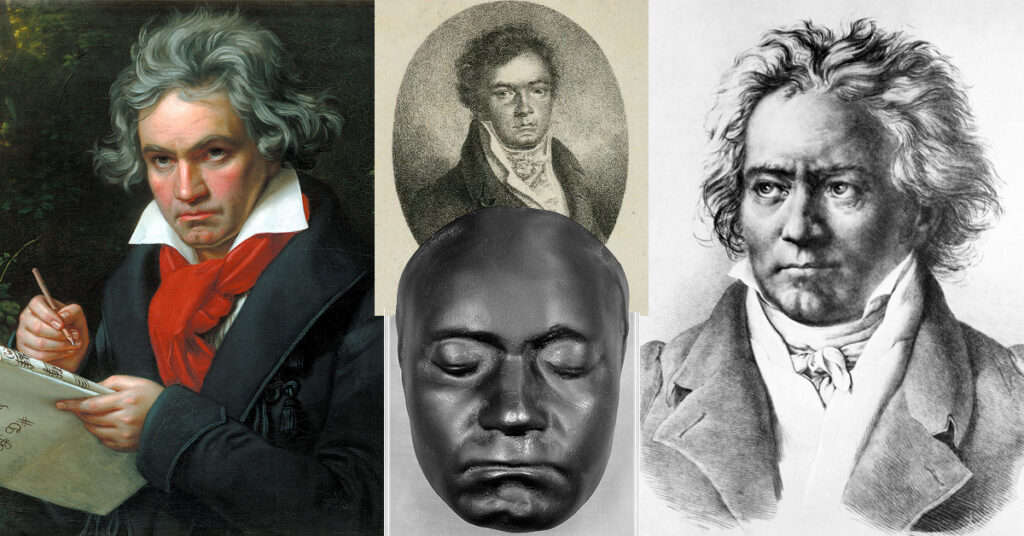

Duh duh duh DUHN! Cue the first measures of Beethoven’s magnum opus 5th Symphony. There is evidence to suggest that the composer was black, or descended from black ancestry, and even a sliver of supporting evidence should give pause to historians and genealogists everywhere.

Let’s step back and take a look at our established Euro-centric narrative. Most of our historical record was written by oppressive forces. In the First Planet-wide Cold War of 1492-1975 (title and dates subject to interpretation) the race for world dominance was won by the European power with the greatest access to natural resources, and the Americas proved to be a literal and figurative goldmine. As a result, the North American population alive and well prior to 1492 was decimated, and the continent’s population wouldn’t return to pre-Columbian numbers until the latter quarter of the 19th century. In those four centuries of peak colonialism the natives’ chances of survival were slim, but cultural death was almost guaranteed. Whether it be Christopher Columbus, or the Sullivan massacre, or the enslavement of African people for the benefit of commerce in the South, the assimilation of whole cultures meant wiping their heritage and traditions out of existence.

This undoubtedly creates a headache for future historians. As Nazi Germany was well known for aryanizing the culture and history of Germany, and later all of occupied Europe, the anglicisation (say that 10 times, fast) of the Americas was arguably just as prevalent, if not more subtle and occurring over a much longer span of time. The whitewashing of noteworthy Biblical characters is a prime example of Western society changing history to match their skin tone. But Beethoven? Taking a page from the Nazi rulebook (and crumpling it into a ball and throwing it into the fire) of course it would make sense to take a genius composer with a vast array of artistic depictions and morph his likeness into something resembling yourself. The “elite” of the Colonial Era had access to printing presses, artists, and writers, and were not afraid to use them. However, written accounts of his parental lineage and physical appearance from his friends and family do exist, which clash with the popular depictions of the genius that we’ve generally accepted as canon. Had we not dug for this contrary evidence, Beethoven would’ve forever been tossed into the pile with the rest of the white historic figures. (Meanwhile, his Black contemporaries – the ones that are well documented as being Black – remain unknown and obscure to all but the most knowledgeable classical music fanatics. See below for some examples.) The fact that this evidence exists doesn’t exactly prove the color of his skin or his lineage as much as it casts suspicion on many of the historic profiles that we’ve accepted as factual.

This reminds me of the unusual phenomena that spread like wildfire through genealogy circles in the not-too-distant past. The claim of Native American ancestry (particularly Cherokee) was born from oppression and later romanticized to the point where it’s almost uncool to not have 1/128th Native American blood. (Never mind that the blood quantum system of measurement is controversial at best.) In reality, if you’re white and descended from European ancestry, and your family has lived in the Americas since Colonial times, there’s a pretty great chance that your ancestors were involved in efforts to genetically whitewash Native American and Black culture, and that also likely means that your genealogic record is much more complete on the European side of your ancestry, simply because Native identity and enslaved peoples’ histories were largely erased as white Americans pushed westward.

If you utter the name “Thomas Jefferson” in a classroom in the ’80s you’d hear a very different reaction than you would in 2020. Our distinguished founding father went from national hero to problematic public figure to rapist of enslaved people within a very short span of time. Predictably the social justice microscope has been aimed at the legacy of Nathaniel Rochester, noted founder of Rochester, New York, and buyer and seller of human beings. At one point the enslaved people that were brought with him from Maryland to New York were more or less overlooked by history. Later, his movement north was regarded almost as that of a conductor on the Underground Railroad; he was bringing them north to free them, he can’t be that bad. In recent years new records have surfaced which paint a clearer picture of what was considered property, among them ledger entries reflecting the purchase and sale of humans, and the unavoidable fact that he kept some people as property long after he reached Dansville, NY. Here’s a fact that I learned minutes ago: in 1800 there were twice as many enslaved Black humans as there were free Blacks in the state of New York. This, the anti-slave Northern state that I once believed had little to do with slavery other than the Underground Railroad. We can thank Quakers and sympathetic lawmakers for making this a safe(r) space for Black residents, enough so that Frederick Douglass called Rochester home and publish the North Star newspaper here from 1847-1851, but this was never a utopia. One only has to read the news accounts of July 1964 to realize Rochester history and reality didn’t always intersect.

What does this mean for the researcher? In short, it means that we need to try harder. We need to be open to other sources which might challenge the popular narrative, especially now that previously unchallenged beliefs about our history are being reviewed under a new light. We need to understand that certain sources were written a certain way to uphold white supremacy. We need to recognize that our current history is still omitting certain facts from the timeline, like the under-reporting of lynchings by white supremacists in 2020, or the atrocious record keeping of Covid-19 cases and deaths in the U.S. And often it means that we often need to become the keepers of history. Memes, personal journal entries, blog posts, and even tweets may one day shed some light on an oft-misunderstood issue of today. In that vein, we need to find the meme equivalent of the era we’re researching. I love using Ancestry.com, Newspapers.com and other sources of mainstream research sources, but I’ve had some of the most fun learning from sitting in the History room at my local library, or pouring through old papers of my grandparents. We need to embrace doubt. Was Beethoven Black? Maybe one day we’ll have proof one way or another, but the fact that it took 2 centuries for new sources to see the light means that there’s likely a lot more we have to learn about topics we think we’re done learning about.

Where were Ludwig von Beethoven’s contemporary Black musicians? Not surprisingly they’re largely omitted from typical public school educations in the U.S. Check out the following: George P. Bridgetower, Le Chevalier de Saint-Georges, and Francis Johnson.