McCrackenville and Lower Falls

Year Incorporated: 1834/1850

Ward: 10

Population: n/a[/su_box]

Whether fortuitous or not, the location of McCrackenville – one of the few original settlements that comprised the original City of Rochester – was directly in the path of commerce. We know by now that Rochester, much like the original 13 colonies of the United States, was much smaller in the beginning. Discussing these settlements was much like discussing California in 1777; history is not limited to what happened in New York or Virginia. Rochesterville, one of those first settlements, made a name for itself in the flour industry. Yet, especially in those early days before the canal, that flour had to leave Rochesterville, pass through Frankfort and McCrackenville, to end up in Kelsey’s Landing or Hanford’s Landing where it would be loaded on a boat for ports afar. It was this commerce, and the stagecoach route that crossed this land, that gave rise to McCrackenville.

I’ve complained in prior posts about Rochester’s reluctance to develop its riverfront. This wasn’t an issue 100-200 years ago, and a prime example is this tract. McCrackenville was, in a way, a peninsula bounded by a creek and the Genesee River. For the first 150 years of its existence the area had a deep ravine, known as Deep Hollow, bordering the land and emptying itself into the deluge of the Lower Falls. The elevated portion was a mix of commercial and residential plots, and descending Hastings Street brought you to the area’s industry, powered by water. An early incarnation of Rochester Gas and Electric operated there, as did a sawmill, a leather tannery, paper company, and a furniture maker.

Before the industry or the grid of streets that hoped to greet eager development, there was a road that would serve significant purpose in the early history of the area, and a valley that was a landmark of strategic importance during the only American war to directly threaten Rochester soil. One of our earliest historians tells of this rickety bridge over Deep Hollow in his 1874 book:

“Deep Hollow;” the two words describe this glen perfectly. To cross it there was erected a frame bridge. I can shut up my eyes now and see the long bents of posts that stood in the gorge, the plates that went across the tops of the several bents, projecting out each side and each having a brace linked into the outside upright post — the cross timbers below and all the way down, a network of braces the upright posts rising, say, four to five feet above the bed or roadway and supporting stringers across their tops that were studded with short studs to which were nailed boards to form a railing — the plank, the old warped-up at the ends, sprung in the middle, uneven, rattling covering on the stringers that formed the roadway — and lastly the deep mud-holes at each end, in to which every animal and vehicle must be plunged in getting off or on — this is some idea of the bridge, which to us young travelers had a deep interest.

“A Boyhood Adventure” by Edwin Scrantom, 1874.

In 1814 the conflict between the British and Americans had dragged out long enough to see enemy warships off the coast of Charlotte. The alarm bells had been rung and a militia of a mere 33 able-bodied persons had been formed to march across that bridge and eventually to the village on the lake. The bridge at Deep Hollow, being one of the last defenses for the Rochesterville settlement, had a guard stationed at the end as well as 2 canons. As a last resort, the guard was instructed to sabotage the planks, rendering the bridge impassable. (More on the conflict at Charlotte in a later article.)

There will be discussion in a later article about the lives of the Seneca people who lived here, but for now let’s step back to the beginning of the “frontier” settlement. Soon after the War of 1812 had ended, when the coast was literally clear, three brothers from Batavia eyed an available tract of land along the Genesee. Although Rochesterville was situated between the Upper- and High Falls, there was huge potential for a similar settlement to flourish between the Middle and Lower Falls. David McCracken, along with brothers William and Gardner, purchased the tract and set out to make a name for themselves. William opened the McCrackenville Tavern (later called the North American Hotel), oddly located in neighboring Frankfort settlement. Gardner opened a flour mill, and David – besides seeing to the affairs of the settlement – was a doctor. One by one lots were sold off, and houses and businesses began popping up. The settlement even reached the important milestone of requiring a cemetery, which was established at Driving Park and Lake Ave (and later abandoned). McCrackenville was booming; what could possibly go wrong?

As was the practice with any moving body of water at the time, the rule seemed to be “if it flows away from you, dump your sewage into it”. Deep Hollow Creek originated as far as Gates Center, crossed the Erie Canal, before dumping into the Genesee. This was an easy sewage disposal route for much of the west side city and towns, and the West Side Trunk Sewer was crudely laid, opening into the city portion of Deep Hollow. It didn’t take long for residents to complain about the smell. After much back and forth the West Side Trunk was completed and sewage was routed away from McCrackenville. By this time the Erie Canal had been plotted through Rochesterville, eliminating a sizeable portion of the commercial traffic. McCrackenville was down but it wasn’t out.

McCrackenville’s eventual integration into the new city of Rochester proved to be mutually beneficial. The expansion of the western boulevard toward Charlotte meant the neighborhood was less a remote village and more of a central neighborhood. Industry jumped on the opportunity to utilize the river and all the power it had to offer. Mills were erected with haste right at the water’s edge and, according to plan, residences filled in just up the hill. Schools and churches would follow. The Greater Harvest Church which sits prominently at 121 Driving Park began in 1895 as Glenwood Methodist Church. The congregation had a much smaller structure built at the corner of Driving Park and Pierpont and remained there until 1908. In 1905 construction began on the massive church that exists today.

I was quite intrigued with an older building at 694 Lake Ave. Sure enough a search of Newspapers.com yielded an interesting timeline. It looks to be an ordinary warehouse now, but in the ’40s Studebakers were sold from here. Prior to that it was George Bantel & Sons which sold horses for city transportation and farm use. In the late nineteenth century “street sprinkling” was what we’d refer to simply as street cleaning, and instead of those Zamboni-esque trucks with spinning brushes that we see today you’d see a horse-drawn cart with a barrel of water mounted on the back. In 1877 George Bantel & Sons made $14 per week cleaning the filth off of Lake Ave alone, and apparently they were good enough at the task to be awarded contracts for many of the streets in the northwest part of the city.

The beginning of the end for McCrackenville’s industry was marred with tragedy and unflattering news. A quick scan of headlines from the Democrat and Chronicle yields the following stories:

- On June 21st, 1949 there was an uproar over a man seen heading into the gorge with an infant. The man acted suspiciously, and had reportedly kissed the child on the forehead before hurriedly making his way downhill. He reappeared a short time later, sans child, and search parties reported no luck finding the baby.

- In 1954 the public learns that Kodak toxins have “grossly polluted” the waters between the Lower Falls and Lake Ontario. A new water treatment plant will be installed near the Veterans Memorial Bridge.

- In July of the same year 6-year-old Michael James Carey falls into the gorge and survives. His sister had tossed one of his comic books over the fence and the boy ventured to retrieve it. He was saved by an outcropping of rock which had snagged his clothing.

- In June of 1955 Gerald Joyce, age 9, perished after he fell 75 feet into the gorge. He was returning from a morning at the nearby YMCA and ventured too close to the edge.

- In 1958 a 2-alarm fire guts a couple floors of the Barnard and Simonds furniture factory.

- Three years later a group of residents wins a battle to deny the current owner of the furniture factory the right to store and dismantle old cars on the property.

- In 1964 the owner of the old furniture warehouse at 6 Hastings St, having since won the right to store and dismantle cars on his property, was now facing yet another fire. This time young arsonists were to blame. The old autos seemed to have a multiplying effect on the inferno, and the blaze had attracted onlookers and firefighters from miles around.

- A 1967 D&C headline reads “Junk Piles – In and Out – Mar River’s Beauty”.

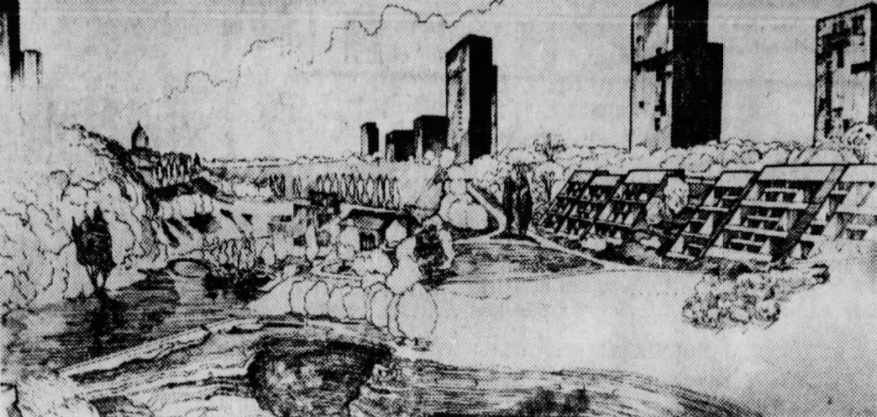

Efforts began in the early ’60s to reverse the decline of the Lower Falls area. Deep Hollow would be filled in with dirt and rubble from the excavation of the Midtown Plaza parking garage. In 1962 the first of multiple plans for high-rises was unveiled. Mayor Lamb requested funding to turn the unwanted auto salvage yard into Lower Falls Park. In August of 1967 efforts to purchase the land for a playground fail and the city moves ahead to condemn the parcel. The same year another riverfront improvement initiative would introduce high rises dotting Lake Avenue while futuristic-looking condos would run parallel to Hastings Street and the gorge face.

Ultimately the simplest plan won, and Lower Falls park was born. The south end of Hastings Street was blocked off and left to crumble while the north end was repaved as a pedestrian path. Besides the Hastings retaining wall, the path, and RG&E, the only remnants of the McCrackenville industrial tract are the walls of an old millrace. Perhaps some enterprising future generation will excavate the site and discover the foundations of the old buildings which lay dormant under our shoes, however one does not have to venture far to find relics from the old auto salvage yard. I don’t condone risking one’s life to hike deep into the river gorge, but if one were to find one’s self at the river bank you’d notice a landscape dotted with metal artifacts.

An art installation in Lower Falls Park

The remnants of Hastings Street

Since the conversion in the late ’60s the spot remained a “passive park” meant for viewing instead of experiencing. Visitors were often met with high grass, weeds and “No Trespassing” signs put up by RG&E. Residents and city officials launched Rediscover the River Days in the early ’80s to help remind area residents of the beauty the Genesee had to offer, but challenges still remained. Greenpeace, the environmental action group, protested RG&E in 1985 after a toxic sludge was found accumulating between the Middle and Lower Falls. This sludge, a byproduct of coal tar, would ooze up through the rocks and mix with the water around McCrackenville and Maplewood Park. RG&E had discovered the toxin when testing soil for a 12-foot diameter underground sewer tunnel near Ambrose Street, the site of a long-forgotten landfill. As if there wasn’t enough reason to avoid the river gorge, in 1989 the city reportedly hauled out 100,000 pounds of fish carcasses from the shore around Lower Falls.

Then-mayor Ryan saw a crisis brewing. He convened a Lower Falls Committee in February of 1990 to deal with some of the challenges the area was facing. Soon after the River Romance campaign, a re-branded effort akin to Rediscover the River Days, would turn up the volume on everything positive the Genesee had to offer. Hastings Street was improved, and connected via the RG&E dam at Middle Falls to Brewer Street on the east bank of the river. The grass and weeds were trimmed. In 2001 the unforgettable public art sculpture entitled The Seat of Forgetting and Remembering was installed, along with educational signage about the area’s history. The Lower Falls area experienced a minor renaissance, if only for a while.

Not much has been done here in almost two decades, but as of this writing that may soon change. The Genesee Riverway Trail Feasibility Study of 2006 and the Local Water Revitalization Program of 2018 both identify Lower Falls Park as a target area. While much of the recent energy has been on downtown riverfront and the Roc the Riverway initiative all of these enhancement projects link with the river parks to the north. Personally I’d love to see improved access to the lower gorge area and an improved – and safer – falls overlook. This place is an asset that the city struggles to maintain, and although things have improved tremendously in the last 50 years, it’s a far cry from the energy of the first 100 years of McCrackenville.

Another excellent article onthe history of Rochester. I lived in that area fora number of years and never knew it was called McCrackenville. Kudos to the author for making it fascinating reading.