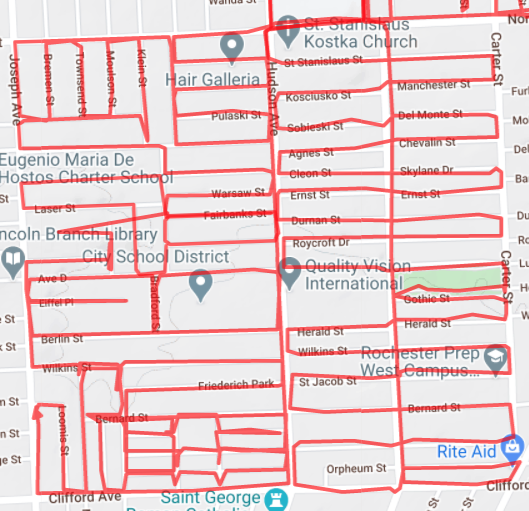

14621 part 2: Polish Town

Year Incorporated: 1874

Ward: 17/22

Population: n/a[/su_box]

Thanks to the strong Polish-American community in Rochester and their excellent record keeping, I was eager to dive into the history of this neighborhood. Though, when it came to riding the 22+ miles of roads, I found myself face to face with the beast that I had previously had the fortune of avoiding: winter weather in Rochester. Confession time: this was my first time riding the bike in the snow. Prior to this I had one last hurrah on 2 wheels in mid-October, then the bike would go into storage til April. Everything east of Hudson was traversed in our unseasonably-mild November; everything west on December 9th. I came out of the experience soaking and unable to see out of my glasses, but victorious nonetheless. On the bright side, I’ve proven to myself that I can ride in mild Winter weather. On the other hand, I had to ride with poor vision and because of this the bulk of my pictures were taken on the Eastern half of the neighborhood. Apologies to the Western half, though there is one really cool old building I was able to get a photo of, which I’ll mention later.

Polish settlement in Rochester first came in small waves, and later a tsunami, and was often tied to struggles in Poland. The first wave began in the 1830s as a result of the Polish–Russian War, and thus Polish Americans were very much a part of our city’s formative years. The January Uprising of 1863 drove another huge wave here which didn’t subside until after World War II. As we’ve seen with other immigrant groups at the time, the large waves create equally large real estate booms as people from similar origins prefer to cluster together. And so a previously patchwork diaspora throughout Monroe county began to coalesce in this section of the city that, til that time, consisted mostly of open fields.

We begin our printed word tour as the city grows, pushing outward from downtown. In 1861 The Saint Joseph’s Church congregation (whose former home is now the shell of a church we admire on Franklin Street) purchased acres of “meadows” north of Clifford Avenue for an orphanage and new church. Before the orphanage was actually built it was relocated downtown, and so the new plan was to construct a grand church, the fifth for the German-Catholic population and 10th Catholic church within city limits. In 1867 a smaller church structure was built on the land, but it soon became inadequate for the needs of the congregation and so in 1876 the Church of the Holy Redeemer was constructed. The building would receive landmark status 112 years later.

The congregation swelled in size to nearly 25,000 members, and was lead by pastors with names such as Oberhoelzer and Staub, reflective of its largest ethnic demographic, though it wasn’t exclusively German; Lithuanians, Poles and several other Baltic populations were drawn here. During this time the original church building had been transformed into a parochial school, lead by the School Sisters of Notre Dame from 1869-1975. And so the beginnings of this mainly Polish Tract had its roots in other European origins, mainly Germans. The Rochester Abendpost, a German language newspaper (1902-1967) was widely distributed here, and the map around the southern half of this tract is dotted with German street names.

If the Church of the Holy Redeemer anchored the southern end of the neighborhood, Saint Stanislaus Kostka Church was the northernmost anchor. Twenty two years after the Catholic community built Holy Redeemer a wave of new Polish immigrants laid the first stones of St. Stanislaus in a remote area of the city populated with fruit trees, wildflowers and wild ducks. Hudson Ave north of St. Jacob Street, and most of Norton, were dirt roads. Random houses dotted the landscape, and a creek ran through the middle of the block.

The Polish community had some interest in this section of the city early on. A number of families had settled in the North Clinton area, and many of the young adults labored at the Moulson Nurseries in Irondequoit opposite Norton St from their future tract. A group known as the Society of St Casimir came together to represent the Polish parishioners of St. Michael’s and other nearby Catholic churches. They managed to raise $3500, a sum that would afford them 12 lots to the west between Remington, Weaver, Joseph and Norton, yet a month after the purchase they worked out a trade, swapping that block for the open land to the east – a tract suitable for the new church and 100 or so families. They surveyed and marked out streets and named them for Polish heroes like John Sobieski (the 17th century King of Poland), Tadeusz Kościuszko (who was a hero in both the American Revolution and the Polish-Russian War) and Casimir Pulaski, the 18th century “father of American cavalry”.

The Saint Stanislaus Church that we admire today was constructed beginning in 1907. Since the dedication of the original church the size of the congregation had grown by a factor of more than 20. Once again funds were raised and plans were drawn. Teams of volunteers did most of the dirty work, and the only heavy equipment used was a horse-drawn shovel. The cornerstone was laid in a widely-attended ceremony in July, 1908 and the project was finished a year later.

Businesses soon sprang up to meet the needs of the new town-within-a-city. Stephen Zielinski opened a lumber yard, and provided the materials for over 500 of the neighborhood’s new homes, often extending credit in ways that would be unheard of today. Brodie’s Meats, opened in 1898, was a well-known producer of kielbasa, and operated by the Brodowczynski family. Walter Wojtczak opoened Wojtczak’s Bakery in 1915. Originally launched as a delivery-only business, it eventually ended up in its well known home at 990 Hudson Ave. Ownership switched hands in the late ’60s to an Italian family, but the Polish recipes remained the same. Meanwhile the original Wojtczak family opened a new pastry shop on Titus Ave. The original bakery would switch hands a couple more times until closing permanently in 2005. Countless other businesses with Polish proprietors dotted Hudson Ave and cross streets during the late 19th and most of the 20th centuries.

There’s an interesting history of public libraries in this neighborhood, which ties in with the Socialist movement so prevalent in the early part of the 20th century. Beginning in May 1905 the Rochester Alliance of Polish Socialists organized themselves around the free pursuit of knowledge, particularly in the realm of politics. With their own funds they rented space on Bernard Street and filled the rooms with hundreds of Polish language books and periodicals. The popularity of this resource soared and the tiny location burst at its seams and so, in October 1911 they relocated to a larger space at 818 Hudson Ave, a building which would later be known as People’s Hall (1918) and then Dom Ludowy Polski, or in English “Polish People’s Home” (1922). In 1930 a new city Public Library branch had been announced, to be built opposite St. Stanislaus Church. This was a noteworthy choice of location as it was only the second permanent library in the city, even predating the central library building. The Pulaski Library, as it’s now known, operated from 1931 to 1994. The building itself was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2002 and made the 2013 “Five To Revive” list at the Landmark Society.

On the western edge of this neighborhood is the old Congregation B’Nai Israel (later B’nai Israel Ahavas Achim) Synagogue, located at 692 Joseph Avenue. Built in 1928, it is the second oldest synagogue (current or former) in the city. This 11,000 square foot structure has seen better days, and if all goes according to plan it will be redeveloped into the home of the Joseph Ave Arts and Cultural Alliance. The Joseph Avenue area was once regarded as the center of Jewish activity in Rochester with over 20 synagogues, but over the decades that has changed. The congregation here peaked at around 500 families but dwindled to about 100 in 2004, giving up on the building soon after. The Cultural Alliance bought the property in 2014 and has struggled to come up with the necessary $2.8 million in redevelopment funds ever since.

I think it’s safe to say Polish Town can claim a century of eminence in Rochester, beginning with the first Polish picnic in 1889 all the way to the fall of communism in 1989, which drastically reduced the influx of immigrants. The Polish community isn’t nearly as centralized as it once was a century ago, but they continue to demonstrate their heritage and traditions throughout Monroe County. The Skalny Center for Polish and Central European Studies at University of Rochester, founded in 1994, continues to offer opportunities to university students to connect with Polish heritage. Since 1997 the Polish Film festival has brought Polish media to Rochester. The Polish Heritage Society of Rochester has been in operation since 1919 and continues to represent Polish values and history within the community. Even the picnic continues to this day, albeit in a different form as the Polish Arts Festival.

In many ways the descendants of the original Polish Rochesterians have blended seamlessly with the rest of the community, a fact that might sting in the ears of the first generation to settle here. And, in many ways, new ethnic identities have taken over in their place – I noticed a strong Caribbean presence, especially in some of the newer Hudson Ave businesses (I’m adding Nin’s Restaurant to my list of places I need to sample). In spite of the demographic change, the area will always hold some of its Polish identity, whether it’s in the place names or the sacred spaces or the businesses that are in it for the long haul. Even if all of these went away tomorrow, there’s something about the Polish spirit that knows inherently where home is, and if they can’t find it, give them a field on a muddy dirt road and see what they make of it.

Another excellent report on the history of Rochester. Your skills with the written word make for very enjoyable reading. I look forward to the next chapter with much eagerness.