Corn Hill & the 3rd Ward

Year Incorporated: 1834

Ward: 3

Population: 3177

Distance traveled: 8.38 miles[/su_box]

From 5000 feet (1524m) in the air the shape of Corn Hill resembles an anatomic heart, apposite to its location and history. Closer to Earth we get a sense that there’s something unique about this place. The architecture screams old wealth, and we get a sense we’re communing with Rochester from a bygone era. Many of us only grace this neighborhood once a year in July, and in doing so are liable to miss the many historic markers that dot the area, hidden amongst the tents and tables of the Corn Hill Arts Festival. In reality, those markers only give us a taste of the talent, turmoil and tragedy that this neighborhood bore witness to over the years. These cobbled streets have seen some things over the years, and to attempt to convey everything of significance that’s happened here would take a very long time, so here is an abridged version of the Corn Hill experience.

The heart of old Rochesterville was the intersection known to most as the Four Corners, Buffalo Street at Carroll Street (Main and State today). Immediately south of here was dedicated to industry and shipping, by way of the Erie Canal. South of this area was, from the very early days, known as the fashionable place to reside, earning the name “The Ruffled Shirt District”. When Rochester began to blossom into a real city, its monied residents built their homes largely where the Civic Center is now, and though much of these earliest homes have vanished under the wheels of urban renewal, the remainder of this early housing bull market can be seen in Corn Hill, Rochester’s first residential neighborhood. This mix of canal-oriented industry and nice shirts was, from the time Rochester was incorporated, known as the 3rd Ward. In 19th century terms our focus today is on this area cradled by water and rails.

Let’s go back even further. Corn Hill was likely named after the posh neighborhood in London known as “Cornhill” (compound word with no space), though there is some conjecture that early residents witnessed Seneca tribes planting corn on that particular hill and named it accordingly (which was unlikely, as Seneca tribes would hunt here but farm much closer to home, several miles southeast of here). In reality, farmland seemed for a while to be the natural use for this tract as it was somewhat of an island; the river was to the east, swamps to the west, dense forest to the south and, as of the 1820s, the Erie canal to the north.

After the first wave of settlers established mills, built cabins and taverns, the “elite” of Rochesterville began buying up land and moving here; first, just south of the Canal where the Civic Center Plaza is now, and creeping south from there.

A short list of historic landmarks destroyed by “progress” (and a few that survived)

I’ve made my opinion known about 490 and urban renewal in past articles (see: UNiT) but you’d have a hard time finding a neighborhood that had more of its history destroyed by the wrecking ball than the 3rd ward. In fact, it might be easier to start with a list of buildings that survived the ages. There’s the Brewster-Burke House, constructed in 1849 by Henry Brewster, and in 1886 was purchased by William Burke and family. The house itself is of little historic significance, save for the fact that it’s a rare example of a mid-1800s Italianate house within the city. It currently houses The French Quarter, a rare example of amazingly tasty early-21st century New Orleans cuisine in the city.

Sharing historic designation with Brewster-Burke is the Jonathan Child mansion. This Greek Revival home was constructed in 1837 by its namesake, Rochester’s first mayor. Child was one of those figures who seems to routinely fall in and out of grace in the eye of the public, and I doubt he’d find much favor now. Son-in-law of Nathaniel Rochester, he was appointed (read: unelected) Mayor by the Whig party in 1834, only to resign the next year because his extreme views on temperance were in the minority. He then built a very flashy mansion on his waterfront property, then used his canal access to make a fortune on the coal trade during an economic depression. Child and family didn’t remain in Rochester for long, and the building went through many different incarnations: a boarding house, swanky club, church property, dance hall, offices, and a cafe.

The Hervey Ely Mansion, now belonging to the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), was built in 1837 by Mr. Ely, then a very successful flour merchant. The family was forced to move out in 1841 when the flour market crashed. Dr. Howard Osgood, prominent local theologian and Egyptologist, owned it with his wife from 1871 – 1905. It’s been owned by the DAR since 1920.

The Ebenezer Watts house is that structure that looks completely out of place on Fitzhugh Street as you approach the parking garage. Built beginning in 1825, it’s now the oldest surviving residence in downtown. Watts was an early metalworker and opened one of the first hardware stores in the young village. He was also a Master Mason (not the brick-laying kind) and hid his Masonic papers in the walls, which wouldn’t be found until a restoration project in 1956. In 1837 a young man named Daniel Powers boarded with Watts, clerking at his hardware store for room and board. Powers would later be known as one of the early titans of local commerce, and we know him by the Powers Building that still stands in the heart of downtown. In the 19-teens it was converted to law offices, and a partial restoration was completed in 1948. The Watts House had a brush with “progress” in the 1960s as plans were drawn up for a 25-story Civic Center Tower, but cooler heads stepped in and after many years the house was designated as a historic landmark.

First Presbyterian Church has stood at the corner of Spring Street and South Plymouth since 1871. Designed by superstar architect Andrew Jackson Warner and built by William Gorsline, the structure cost a whopping $85,000 (roughly $1.7 million today). The Presbyterians have had a large presence in downtown since the Rochesterville days, and this particular congregation formed in 1825. Moving twice in the interim, they settled on the current location after a fire destroyed their previous building in 1869. At one point the church had a cemetery located across the street, likely where the jail is now.

The Bevier Building, situated between the Brewster-Burke property and the First Presbyterian Church, is the only remnant from the old RIT campus (see below). It was part of a gift of the estate of Mrs. Susan Bevier, who wished to construct a building for exclusive use of the arts department, and including a gallery, public hall, and museum. Mrs. Bevier was the owner of a significant share of stock in Hathaway and Gordon Brewing Co, which began operations in 1865. Later it would merge with Longmuir Brewing, which started all the way back in 1834. The company ceased operation in 1912. Overall the Mechanics Institute received over $277,000 from the estate, worth nearly $7.7 million after inflation.

National Casket Co., now known as the Court Exchange Building, was once sandwiched between Exchange & Court Streets and the Rochester, Fitzhugh and Carroll Millrace. Built in 1881 by architect Harvey Ellis, it housed the casket company of Samuel Stein, a pioneer in casket design. Prior trends resulted in a plain pine box burial; Stein utilized cabinetmaking practices and a fabric liner to produce the ornate, dignified coffins in use today. President Ulysses Grant’s coffin was made here, along with many other notable figures. Stein’s casket business was launched in 1853 and survived, in one form or another and at this location from its construction until 1984.

Court-Exchange, aka National Casket

The Bevier Building

The “Bubble House”

The Jonathan Child mansion

The Brewster-Burke House

Now, let’s look at what we lost:

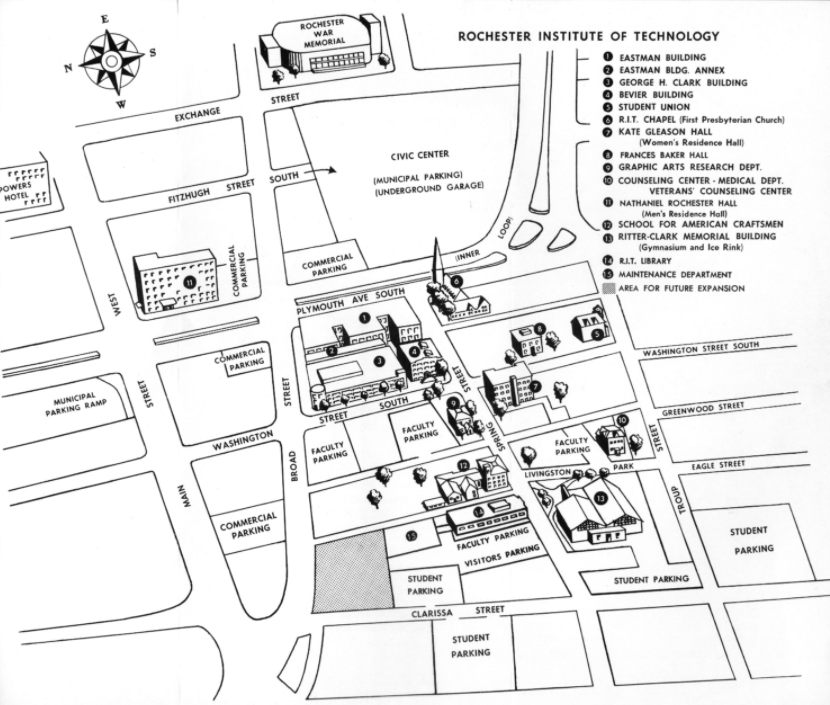

The original RIT

Rochester Institute of Technology began in 1885 as the Rochester Athenaeum and Mechanics Institute, or simply the Mechanics Institute, and the first academic offering was a drawing class. In the earliest days it was less a campus and more a cluster of classes and instructors thrown together to meet the demands of the young and booming industries of late-19th century Rochester. In 1892 the institute had grown beyond its humble beginnings and a permanent building was purchased at Washington Street at the Erie Canal. This campus grew steadily through the first half of the 20th century to meet the demands of the unstoppable technology boom. It was this rapid expansion that sealed the fate of the downtown campus; expansion at the rate necessary to keep up with demand would be very expensive, the land wasn’t always available (especially with the construction of the western portion of Interstate 490 gobbling up huge tracts) and there was an opinion among officials that too much of the area around the downtown campus was “deteriorating”. By November 1961 it was announced that RIT would move from its 13-acre downtown site to a property about 100 times its size in Henrietta. With the move, officials promised improvements such as trees, a dial-up audiovisual library, a 4000-car capacity parking area, and fallout shelters, among other improvements. The old campus is now gone, and in its place is the Rochester City School District headquarters.

Plymouth Spiritualist Church

Here lies the origin of Rochester’s first rap scene, setting of scores of modern-day podcast documentaries, and what was likely to be a tourist trap, marked by an obelisk. Spiritualism in the 19th century was more than a passing fad; Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln dabbled in it, along with scores of celebrities and regular people. There’s honestly so much to write about spiritualism, this church, the Burned Over district and the Fox sisters that I’ll revisit the topic at a later date. The obelisk itself has enough story to tell, and it starts with the Fox sisters, who purportedly communicated with the dead in Wayne County in 1848 through “rappings” at a table. The news of this phenomenon spread like wildfire and the young sisters were forced to relocate to a safer home, that of their older sister Anna at (present-day) 111 Troup Street, before moving again to 59 Plymouth Ave. Within a few years spiritualism had ballooned in popularity, thanks to the actions of the sisters, and in 1854 the Plymouth Congregational Church was built across the street from the sisters’ (now former) home, and would last 100 years before being torn down to make way for the expressway. The obelisk was constructed in front of the old church in 1927 thanks to several significant donors, one of which was Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (of Sherlock fame), himself an ardent spiritualist. The dedication ceremony was held on December 4th of that year as Spiritualist leaders from 28 countries were represented, and included greetings from Doyle. When 490 threatened to level the site in 1954, the obelisk was carefully rolled about 50 feet south to its current location across Troup Street.

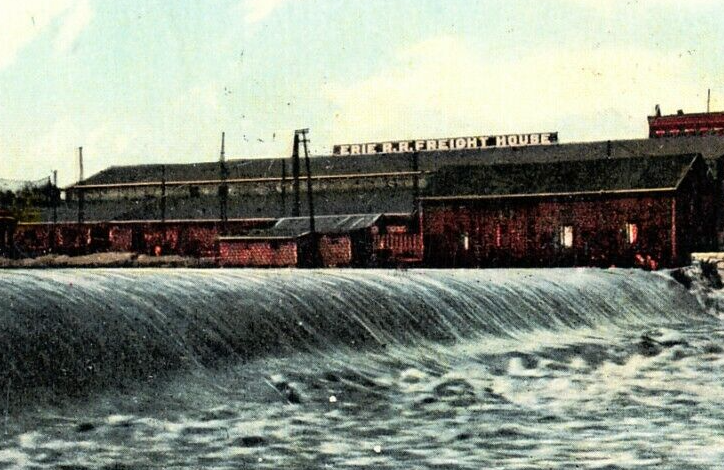

The Erie Railroad

I’ll discuss the impact of the Erie Railroad a bit more when I write about the 1st Ward and 100 Acre Tract, but within the confines of this article’s geography lay an important piece of that infrastructure: the freight house. This was located right smack dab in the middle of the eventual path of the Freddie-Sue Bridge, under which various parking lots shed no clues as to the former use of the space. Its sister building, the Erie passenger terminal, stole all the glory as a gorgeous match to the Lehigh Valley passenger station (now Dinosaur BBQ) on the eastern shore of the Genesee, but credit is due to the freight terminal for feeding the various resource-hungry industries in the city for nearly a century. In fact, all of Corn Hill Landing was former Erie Railroad yards.

A bunch of streets

Pine Street once stretched from Troup to the canal (Court Street) and bisected the Fitzhugh/Exchange block. The central police station, once a modest building measuring roughly 70 feet by 160 feet, exploded in size with the construction of the Civic Center in the early 1960s, completely eliminating Pine. Spring Street suffered casualties as it once spanned from Exchange to Ford Street, now reduced to a few hundred feet, easily missed as you zip past it on the expressway. Troup Street has been chopped up to the point where it no longer connects with itself, serving at one point as an on-ramp and deviating from its old eastern terminus to merge with South Fitzhugh. Favor Street, surrounding Greater Bethlem Temple Church, looks nothing like its original path; once a crowded city block, it now encircles the lonely church structure. A number of original alleys have met the butcher, as well. Hemlock Alley linked Broad Street to Livingston Park, and the only remnants of that are the parking lot of Advantage Federal Credit Union. To imagine what they might have looked like we need not go any further than south of Troup Street, where the neighborhood has – for the most part – been left alone.

Some landmarks weren’t the victims of urban renewal, but met a more tragic fate:

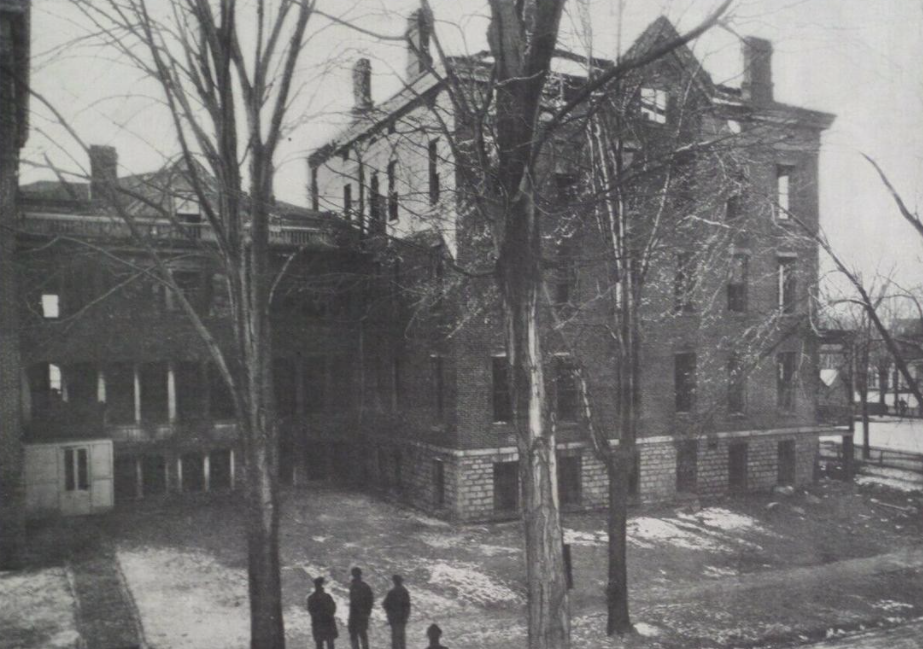

Rochester Orphan Asylum

Browsing through the center of Mount Home Cemetery where the old North section meets the newer southern half, one might notice a peculiar marker reading “In Memoriam, Rochester Orphan Asylum”. Back in Corn Hill there’s a block of homes on Hubbell Park that’s packed a bit denser than the typical neighborhood lot, being of slightly different character than the ancient structures nearby, and largely being built after the turn of the 20th century. These were the homes which replaced the Rochester Orphan Asylum (1843-1901), lost in one of the more tragic episodes of our collective history.

The need for an orphanage came from a tale of a four year old boy that local police officers referred to as “Saucy Bill” who had wandered Main Street alone on a summer day in 1836. As the prospects dimmed on finding Bill’s parents the community struggled to determine his fate. As was often the case back then, the Rochester Female Charitable Society rose to the challenge and collected funds for an orphanage. Originally based on Adams Street, they moved to Hubbell in 1843. The orphanage would take in both parentless children and those with parents who struggled to house them; in the latter scenario, room and board peaked at about $1.50 per week. As of January 7th, 1901 there were 109 children living on premises.

Just after midnight on January 8th a small explosion erupted after gas had leaked from a basement laundry room. The investigating coroner, a Mr. Henry Kleindienst, noted that while the fire was deemed accidental, fault should be attributed to the board of trustees and “lady managers” of the orphanage for not hiring a night watchman. The janitor, he noted, was asked to sleep off-site and had they allowed him to dwell on-premises he may have been able to prevent the loss of 31 lives. Furthermore, the 2 existing fire escapes were inadequate, and many of the windows had been unable to open.

The tragedy made national news and was a devastating shock to local residents. Those in the vicinity of the fire helped in whatever way they could, some even housing survivors until a permanent home could be found. In the end the trustees of the orphanage couldn’t fathom rebuilding on the old site. A new site was selected and five years later a new facility we know today as “Hillside” was opened.

Corn Hill Methodist Episcopal Church

The site at the north end of the public circle has had a fiery history. Now known as End Time Deliverance Miracle Ministry, 144 Edinburgh St has been a holy place since 1854 when the first Methodist church was built here, but had to close shortly after its dedication due to a fire. The building that looks like a castle (professionals might call it Richardsonian Romanesque-style) was built in 1900. It was mostly incident-free until a fire in 1965. After waning membership numbers, the property was then donated to the African Methodist Episcopal church in 1969. Again, fire struck in 1970. The critical blow was dealt on August 7, 1971 when the inside was completely gutted by a 2-alarm blaze. The prior year the building had extensive upgrades to its electrical systems and had no reason to combust without some outside help. Investigations revealed that 3 of the 4 preceding fires had been arson, and the early ’70s saw multiple local Black churches victimized by bombings. This was enough reason for a large portion of the congregation to go elsewhere, which left the church in a tough spot financially. They were able to rebuild, but the original facade couldn’t be utilized for anything beyond a garden wall. If these walls could talk, they’d probably mention Malcolm X, who gave his final public speech here a mere 5 days before being assassinated on a cold February day in Harlem.

Rochester’s Broadway

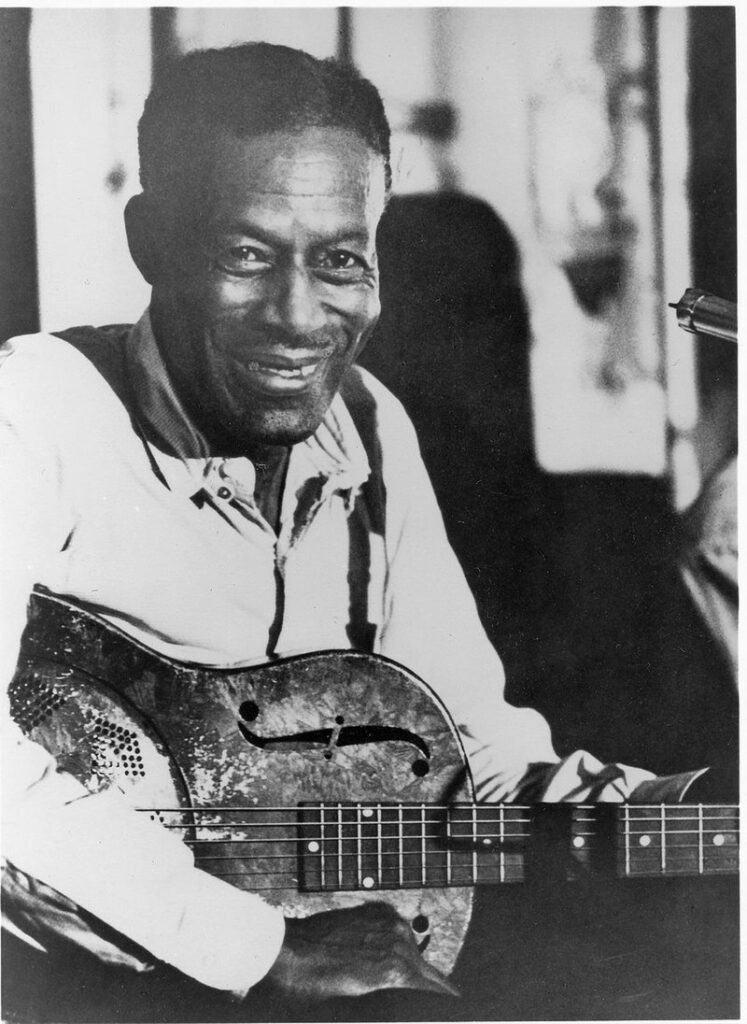

Clarissa Street was an important thoroughfare since the days of Rochesterville, when it was known as Caledonia St. Since then its been at the center of Black Rochester, both culturally and economically. The 19th century saw the first waves of Black settlers building homes here, but it wasn’t until the Great Migration of the 20th century that saw Black culture take hold in such an important way. Music, especially jazz and blues, exploded in popularity after World War II, and this area was next in line behind New York City and Chicago when it came to the Black music scene.

Let’s start with Delta Blues legend Eddie “Son” House. Born in Mississippi some time around the turn of the 20th century, he moved with a girlfriend to Rochester in 1943. He began playing the blues in the ’20s and, though critically celebrated, began selling records during the Great Depression and due to poor sales failed to reach many listeners. His music career languished in obscurity for years. He and his wife moved into an apartment at 61 Greig Street in 1964, and it was soon after that three of his fans tracked him down and convinced him to record once more. His return to blues was well-timed, and put him and his back catalogue into the spotlight. His enjoyed a fruitful career until his retirement in 1974. In the location of his former home stands a marker for the Mississippi Blues Trail, a source of pride for Corn Hill.

Perhaps the hub of this neighborhood’s music scene was the intersection of Clarissa and Troup Streets. In the spot that’s now the Flying Squirrel parking lot stood the Pythodd Club. Opened in 1968 inside a deteriorating 3-story building and known around town for big names and no dancing, the Pythodd was the place to go for the intimate jazz experience. Big names in the scene would pop in after a paid gig elsewhere. The club was owned by Stanley Thomas, who happened to also be the 3rd Ward Democrat Party leader at the time, and politics was a consistent runner-up to jazz in conversations.

2 doors down from Pythodd was originally Dan’s Tavern, owned by Joe Daniels from 1940-1967. Joe was the first Black man to obtain a liquor license in Rochester. After years of success he sold the building to Ruther B. Sheppard, who ran Shep’s Paradise from 1967-2002 and managed to maintain, and later revive, the jazz scene locally. Since then the property has gone through a few different owners, and mostly under the name “Clarissa’s”. This quiet local bar and stage only hints at the talent that has passed through those doors, but the cause of the silence is widely known. Urban Renewal was anything but that for this once booming corner of town. Any time Mr. Shep was asked about the downfall of the jazz scene in Corn Hill, he mentions the constant mess the trucks would make in front of the bar.

Some day I’ll write about the history of benevolent organizations in Rochester, but I can’t write about Corn Hill without mentioning the Elk’s Club that used to occupy the Flying Squirrel building. The Improved Benevolent Protective Order of Elks of the World (IBPOE) was different from the Benevolent Protective Order of Elks of the World (BPOE) in that it allowed Black members from the beginning. Founded in 1906, the Flower City Lodge, as it was known, held all kinds of events and community service around town. They were ‘elves’ on Christmas Eve, hosted dances on Valentines Day, promoted war bonds during WWII, marched in countless parades and held hundreds of ceremonies at 285 Clarissa St. The lodge is closed, and since 2010 the building has been occupied by the Flying Squirrel Community Space, which has taken the community service baton from the Elks and run with it.

There’s a fine short film about the history of Clarissa Street, which I’ve included above. It touches on one of the more tragic chapters of Corn Hill history: 1964, and the Black rebellion. I’m working on a podcast version of the history of that time, but until then there are a few key takeaways for Clarissa Street itself.

The ordeal began in the Joseph Avenue area on July 24th, but by the next day violence had spread to the 3rd ward – the location of all four deaths. The first fatality was, according to the D&C’s Jack Tucker, resulting from “a weird chain reaction sequence” in which the man appeared, helmeted, in the intersection of Clarissa and Atkinson Street. I won’t go into detail about the nature of his death, except to say it was disturbing and unusual. The following 3 fatalities occurred when a helicopter surveying the scene hit the roof of 252 Clarissa Street (across from the Elk’s Lodge), killing the pilot and 2 residents within the house. Multiple acts of heroism saved the lives of 2 helicopter passengers and one man who was seated within a car parked in front of the house. The preventable nature of all four these deaths makes them all the more tragic. An inquest by the Civil Aeronautics Board ruled in January 1965 that the pilot had a blood alcohol content of .08%.

The landscape of Clarissa Street is forever changed. In 1968 Capsule Dwellings, Inc. had purchased the lot where the helicopter had crashed and had built “instant housing” – 16 pre-fabricated 3-bedroom units that only take 32 hours to construct. Necessary housing, yes, but also another nail in the coffin that I’m sure the owner of Shep’s Paradise was referring to. Urban renewal gutted much of the famous street immediately north of here, and also to the south near Mount Olivet Baptist Church (est. 1910).

Certainly much of the resilience of the Third Ward and Corn Hill neighborhood is due to its rich cultural heritage, which has always included Black, brown and white folks since the earliest “ruffled shirt” days. The biggest enemy to the neighborhood, in my opinion, has been the backhoe. The Inner Loop and urban renewal divided the neighborhood in ways that racial or economic stress never could. The constant rumble of construction equipment and poor city policy drove businesses to close their doors. Recent developments, like the Corn Hill Landing complex (2005) have begun to breathe new life into the area without sacrificing the existing architecture, but there’s still room for improvements. The Corn Hill Arts Festival, running almost continuously since 1968, helps to maintain interest in the preservation of this neighborhood. As I’ve noted in many prior examples, the residents are the driving force behind the energy of the area. They are responsible for the continued success of Corn Hill, and with a renewed focus on preservation, we will likely enjoy this neighborhood and its character for another 200 years – hopefully without the ruffled shirts.

I lived and worked in the Corn Hill neighborhood and this article brought back many memories. Another great account of Rochester history.